Fionnuala O’Neill Tonning: «Idols and Iconoclasts: Artistic Legacies of Luther’s Reformation»

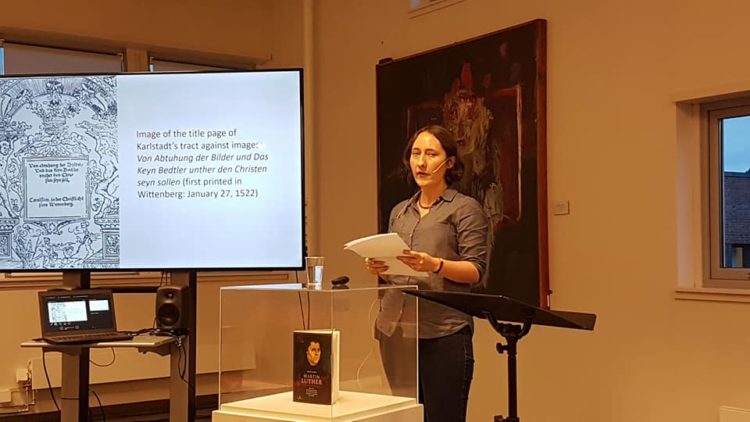

This presentation explored Luther’s ideas about religious art, his attitude to iconoclasm (the destruction of religious images), and the influence of these ideas in England. It began by describing how Wittenberg experienced outbreaks of religious iconoclasm (Slide 2), which were probably influenced by Luther’s radical colleague Andreas Karlstadt (Slide 3). Luther himself was far less hostile to images, although he did think that they could sometimes lead viewers into idolatry (Slide 4). Religious art continued to be created in Wittenberg, including by Luther’s friend Lucius Cranach the Elder (Slide 5), but it was increasingly influenced by Luther’s ideas. Art historian Joseph Leo Koerner has suggested that Cranach aimed to create religious art that was “unsuitable for idolatry” (Slide 6). Note how Cranach’s art expresses new Reformed ideals. Instead of creating emotionally-charged devotional imagery designed to encourage the viewer to meditate on it as late medieval art often does, he focuses instead on instructing the viewer, showing images of religious books and preaching (Slide 7).

In England, where Reformation iconoclasm was more severe than in any other country except Scotland, Luther’s moderate approach became something of an embarrassment for those committed to serious image reform. In his life of Luther the English martyrologist John Foxe attacked theological conservatives who cited Luther in defence of church imagery (Slide 8). Foxe argued that Luther hadn’t really been tolerant towards religious imagery at all, but had had to be politically cautious at the time.

Attempts to reform religious imagery in England weren’t confined to sculptures and paintings: they included images in religious theatre too. The Reformed playwright and campaigner John Bale (Slide 9) wrote plays aiming to reform the stage, just as Cranach had tried to reform religious paintings. Just as Cranach had included pictures of the Bible in his paintings, so Bale puts the character Evangelium (the Gospel), centre-stage in one of his plays (Slide 10). In this anti-Catholic play, called Three Laws (Slide 11), Bale includes references to contemporary iconoclastic events that would have been familiar to his audience, such as the destruction of great cult images and Catholic relics like the Holy Blood of Hailes (Slide 12). Perhaps drawing on Luther’s famous image of the ploughman reading his Bible, Bale argues that the greatest threat to the power of the Catholic Church lies in teaching ordinary people to read the Bible (Slide 13). Bale wants his audience to believe that the Reform movement has burst upon Europe like a great light breaking through spiritual darkness (Slide 14). He is one of the earliest historiographers – and propagandists – of the Reformation, and writings like his continue to influence popular ideas about the Reformation and about medieval religious culture even today.